| Species name | Chamaeleo calyptratus |

| Nominate species | Chamaeleo calyptratus calyptratus |

| Subspecies | Chamaeleo calyptratus calcarifer |

| Common name | Veiled chameleon |

| Local name | Gurafah (Arabic) |

| Author | Chamaeleo calyptratus calyptratus: DUMÈRIL & BIBRON 1851 |

| Author | Chamaeleo calyptratus calcarifer: PETERS 1869 |

| Etymology | Chamaeleo is derived from the Greek “Chamae” (small or crawling) and “Leo” (lion). Calyptratus refers to the Greek “Kalyptos” (hidden or disappeared). “calcarifer” comes from the Latin “calcar“, the name means something like “with spores” |

| Taxonomic history | 1851 – Chamaeleo calyptratus – DUMIRIL & BIBRON 1865 – Chamaeleo calyptratus – GRAY 1984 – Chamaeleo calyptratus calyptratus -HILLENIUS & GESPERETTI 1986 – Chamaeleo (chamaeleo) calyptratus calyptratus – KLAVER & BÖHME 1999 – Chamaeleo (chamaeleo) calyptratus – NECAS 2009 – Chamaeleo calyptratus calyptratus – TILBURY & TOLLEY 1869 – Chamaeleo calcaratus – PETERS |

| Systematics | Chamaeleo calyptratus is related to species such as Ch. africanus, Ch. arabicus, Ch. calcaricens, Ch. zeylanicus and Ch. chamaeleon ssp.

nominate species Ch. capyptratus calyptratus subspecies Ch. calyptratus calcarifer

|

| Typus | Ch. calyptratus calyptratus: Syntypes: MHNP 6522 male, MHNP 6634 male and MHNP 6633 female.

Ch. calyptratus calcarifer: Syntypes: CAC140397 male, CAC134167 female, CAC135118 female. |

| Terra typica | Ch. calyptratus calyptratus: région du Nil, Africa

Ch. calyptratus calcarifer: southern Arabian peninsula |

| Distribution | Chamaeleo calyptratus calyptratus:

Yemen. Chamaeleo calyptratus calcarifer: Southwestern Saudi Arabia (Asir province) (fide Fritz & Schütte 1987: 23).

|

| Macro-habitat | Chamaeleo calyptratus calyptratus:

Montane subtropical acacia forest, farmland, plantations, vegetation on roadsides, in valleys of mountains. Chamaeleo calyptratus calcarifer: Wooded areas on the foothill and valleys of mountains. |

| Micro-habitat | Trees, shrubs, secondary vegetation, agricultural vegetation |

| Perching height | 0-20m. Babies in low vegetation, such as grass and bushes. Adults in Bushes and trees. |

| Daily activity | Basking in the early morning and late afternoon

During the noon they stay in shade and halfshade hunting for prey. Only dominant males expose themselves to the intense sun at noon |

| Population density | high |

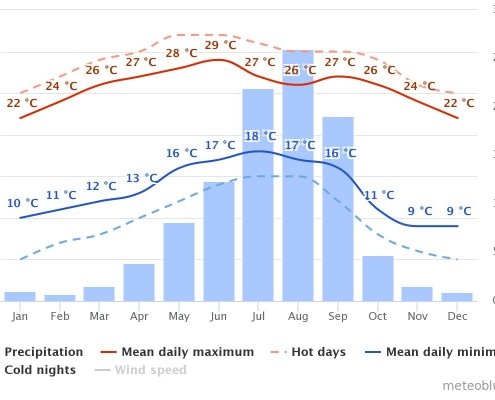

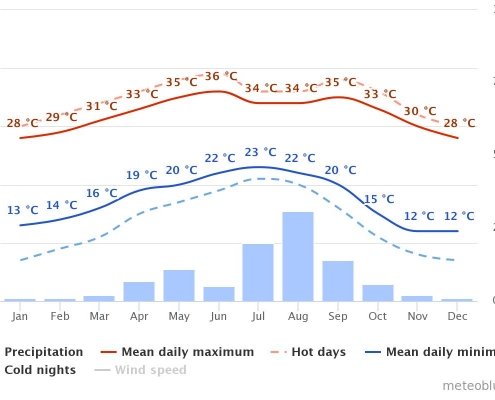

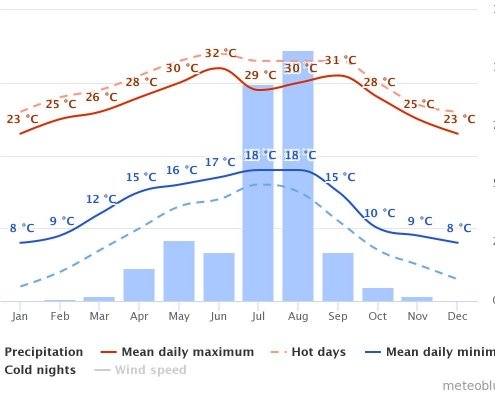

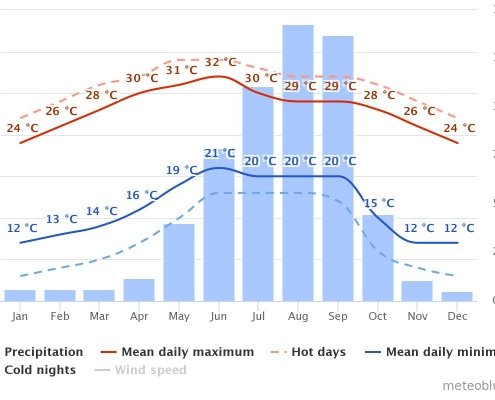

| Climate | subtropical to tropical climate

Rain-Season: April to August Dry-Season: September to March |

| Humidity | Daytime: 20- 50% Depending on season

Nightime: 90-100% over the whole year |

| IUCN status | Least concern due to its tolerance of a broad range of habitats.

The pet trade does affect wild populations as all animals in the trade have a captive origin |

| Conservation | No conservation projects |

| Cites | Cites Ap. II |

| Description | Size:

Ch. calyptratus calyptratus: Males around 54 cm (21”) Females around 40cm (15”) Ch. calyptratus calcarifer: Males around 47cm (18”) TL longer than SVL in both sexes. Casque and crests: Casque high Parietal crest (convex) and lateral crest distinct Thin occipital lobes present Rostral crest distinct, each terminating isolated at the snout-tip Supraorbital ridge continues posteriorly as short lateral crest Gular and ventral crest distinct, consisting of come shaped tubercles which decrease in size posterior and reaching to the cloaca Dorsal crest distinct, consists of a row of cone-shaped scales which decrease in size posteriorly. Ch. Calyptratus calcarifer differs from the nominate form, by having a lower casque. The gular and ventral crest is smaller. Visit the Species gallery for more pictures! |

| Scalation | Homogeneous with granular scales |

| Color | Ch. calyptratus calyptratus:

basic color varies in different shades of green, blue and yellow 4-5 vertically dark bands, if excited males show 3 yellow bars Tail banded with 18-20 dark bands Limbs also banded. The eye turret has dark green radiating lines. Ventral crest is white. Gravid coloration of females: Dark black coloration with vibrant yellow markings and turquoise/ yellow dots.

The sub species differs from the nominate species by not having as bright colors and markings. Color-aberrations are possible in inbred animals of Chamaeleo calyptratus calyptratus |

| Sexual dimorphism | Mature males larger than females

Casque height in males is higher, scales of dorsal- and tubercles of gular crest are more prominent in males. Tarsal spur on each hind foot and a hemipenal bulge are present in males. In rare occasions the tarsal spur is present in females too |

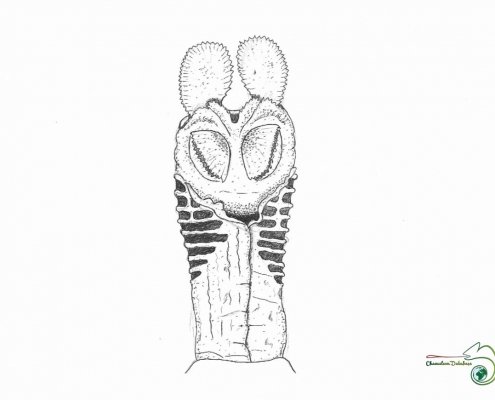

| Hemipenis | Hemipenis is club-shaped and pedicel constitutes one-third of the entire hemipenis. “Sulcal lips” are strongly developed and partially decorated with rows of papillae. Truncus is calyculate, ie. there are calyces. At the bottom of the root there are parallel grooves that gradually connect and close the elongated calyces that sit halfway up the pedicle and apex. Apex ends with a pair of large semi-circular rotulae. Right in the middle, under these rotulae is an extremely serrated crest and underneath this crest are two pairs of less tight-fitting rotulae All rotulae have denticulated margins. Hemipenis at Ch. Calyptratus calcarifer is similar to that of Ch. calyptratus calyptratus, but distinguishes itself in that the two pairs of smaller rotulae are more prominent and the rear (asulcal) rotulae are more round. (Klaver & Böhme 1986) |

| Lungs | has a small skin membrane at the top front of the lung

Two large septa, close to the main bronchi, devide the lung into it into three open chambers – the upper, middle and lower. At the top and front of the lung there are also partly three small septa. The underside of the lung has seven finger-like pockets where some of them branch. |

| Karotype | Unknown. |

| Aggression | Aggressive |

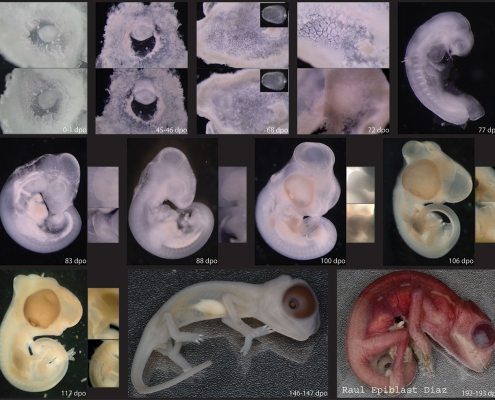

| Parity | oviparous |

| Breeding season | July – August. |

| Gestation period | Gestation period around 1 month. |

| Incubation period | Incubation period 7-9 months |

| Hatching season | Hatching period. March – April. After the first rain. |

| Clutch size | Nature 15-45. In captivity10-120 depending on the size of the female and feeding schedule

Eggs are burried in 10-15cm depth. |

| Hatchlings size | 65-84mm. |

| Sexual maturity | 4-5 months, depending on the size. |

| Courting behavior | Males: head nodding, flatten if the body, swing his tail and show bright colors.

None receptive females will turn dark and gape.

|

| Encrypting behavior | The basic camouflage of Ch. calyptratus lies in its colors that match the vegetation. |

| Feeding behavior/Diet | Small insects up to 3cm

Mostly Flies, bees, wasps, beetles, moths, caterpillars, butterflies, snails, and grasshoppers Larger Individuals can prey sometimes on small vertebrates

|

| Lifespan | 8-9 months in nature. Most animals only survive one Rain-Season, around 8-9 months, due to the harsh conditions in the dry-Season. |

| Captive requirements | Single housed due interspecific aggression

Terrarium size: For adults: At least a netto volume 3x2x3 (LxBxH) of the total length + additional volume if soil is used. Juveniles can be raised in 50x50x80 Terrarium Type: Good ventilated highland terrarium with dense vegetation (Acacia, Schefflera, Ficus, Asparagus) and lots of vertical and horizontal branches. Living plants are important, as they provide shade from the sharp UV light and offer a place to hide in. Temperature: Rain season: 24-28°C at daytime 16-18°C at nighttime Dry season: 19-23°C at daytime 12-15°C at nighttime Basking-spot: 30°C Humidity: Hydration (in general): Fogger running for several hours each night. Hydration supplement, as a precaution: Misting in the morning and evening for 1 minute (mister), depending on whether there are drainage in the bottom. A dripper can be used in the morning and evening, as a hydration supplement. In rainy season: Misting the enclosure one time in the afternoon for 1 minute (heat lamps must turn off 30 minutes before misting and turn on 30 minutes after misting). (Health issues) Lightning: A heating spot bulb concentrates the heat somewhere and allows chameleons to find cooler areas. However, the heat lamp must be placed in a place where the animal cannot reach it, otherwise it may get burns. UVB has an important role, as it allows the animal’s body to convert D2 vitamin, from the diet, to D3, and plays an important role in the absorption of calcium. Artificial lightning can be achieved with several types of light sources. There must be a heating area where the animal can warm up the body. Here, a spot bulb is recommended as it concentrates the heat somewhere and allows chameleons to find cooler areas. However, the heat lamp must be placed in a place where the animal cannot reach it, otherwise it may have burns. An example of how to combine the lighting. Lighting: 6500k T5/ fluorescent -tube 6% UVB T8/T8 fluorescent-tube 50w halogen spot for basking HQI-Bulbs Lightning for 12 hours per day. |

| Incubation | Eggs are buried 10-15cm into the soil

Method 1 1.5 months 24-25°C 2 months to decrease temperature from 25 to15°C 2 months 14-15°C 2 months to increase temperature from 14°C to 24°C until hatching 24-25°C Incubation period depends on the temperatures. Lower temperatures results in longer incubation period. Higher temperatures results in shorter incubation period, but smaller hatchlings. Incubation eggs in a more natural way, by simulating seasons (see above), results in a incubation period of 7-9 months. Temperature-fluctuations of 1-2°C (Day/Night) and changing soil-humidity (rain/dry-season) increase |

| Source | Andrews, R.M. & Donoghue, S. (2004). Effects of temperature and moisture on embryonic diapause of the veiled chameleon (Chamaeleo calyptratus). J.Exp. Zool. Part A, 301A, 629–635.

Andrews, R.M. (2005). Incubation temperature and sex ratio of the veiled chameleon (Chamaeleo calyptratus). J. Herpetol., 39,515–518. Andrews, R.M. (2007). Effects of temperature on embryonic development of the veiled Andrews, R.M. (2008a). Effects of Incubation Temperature on Growth and Performance of the Veiled Chameleon (Chamaeleo calyptratus). JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL ZOOLOGY 309A 435–446. (2008) Andrews, R.M. (2008b). Lizards in the slow lane: Thermal biology of chameleons. Journal of Thermal Biology 33 (2008) 57–61 Andrews, R. M., Brandley, M. C. and Greene, V. W. 2013. Developmental sequences of squamate reptiles are taxon specific. Evolution & Development, 15: 326–343. doi: 10.1111/ede.12042 Bonetti, Mathilde 2002. 100 Sauri. Mondadori (Milano), 192 pp. Braun, S. 2010. Bau eines naturnahen Schauterrariums für ein Jemenchamäleon. Reptilia (Münster) 15 (84): 40-43 Diaz Jr, Raul E.; Christopher V. Anderson, Diana P. Baumann, Richard Kupronis, David Jewell, Christina Piraquive, Jill Kupronis, Kristy Winter, Federica Bertocchini, and Paul A. Trainor 2015. The Veiled Chameleon (Chamaeleo calyptratus Duméril and Duméril 1851): A Model for Studying Reptile Body Plan Development and Evolution. Cold Spring Harb Protoc; doi:10.1101/pdb.emo087700 Duméril, A.M.C. & A. H. A. Duméril 1851. Catalogue méthodique de la collection des reptiles du Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle de Paris. Gide et Baudry/Roret, Paris, 224 pp. Fischer, Martin S.; Cornelia Krause, Karin E. Lilje 2010. Evolution of chameleon locomotion, or how to become arboreal as a reptile. Zoology 113 (2): 67-74 Fritz, J.P. & Schütte, F. 1987. Zur Biologie jemenitischer Chamaeleo calyptratus DUMÉRIL & BIBRON, 1851 mit einigen Anmekungen zum systematischen Status (Sauria: Chamaeleonidae). Salamandra 23 (1): 17-25 Gibbons, Whit; Judy Greene, and Tony Mills 2009. LIZARDS AND CROCODILIANS OF THE SOUTHEAST. University of Georgia Press, 240 pp. Glaw, F. 2015. Taxonomic checklist of chameleons (Squamata: Chamaeleonidae). [type catalogue] Vertebrate Zoology 65 (2): 167–246 Gray,J.E. 1865. Revision of the genera and species of Chamaeleonidae, with the description of some new species. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. (3) 15: 340-354 Hildengagen, T. 2005. Zur Freilebende Chamaeleo (Ch.) calyptratus auf Maui. CHAMAELEO 15(1): 8. Hillenius, D. 1966. Notes on chameleons III. The chameleons of southern Arabia. Beaufortia 13: 91-108. Hillenius, D., & Gasperetti, J. 1984. Reptiles of Saudi Arabia. The chameleons of Saudi Arabia. Fauna of Saudi Arabia 6: 513-527 Junius-BOURDAIN, Fany 2006. CAMÉLÉONS : BIOLOGIE, ÉLEVAGE ET PRINCIPALES AFFECTIONS. Thesis, ÉCOLE NATIONALE VÉTÉRINAIRE D’ALFORT, 189 pp. Kwet, A. & S. Hoby 2011. Wie wichtig sind UV-Licht, Vitamin- und Mineralstoffpräparate? Neue Erkenntnisse über Knochenstoffwechselerkrankungen und ihre Prävention am Beispiel des Jemenchamäleons. Reptilia (Münster) 16 (88): 60 Lane, Rob 2004. Colourful Characters. Reptile Care 3: 22-25 Leptien, R. 2003. Getting started keeping chameleons. Reptilia (GB) (26): 11-14 Love, B. 2008. Doktor Frankensteins Arbeit geht weiter. Reptilia (Münster) 13 (70): 16-17 Love, B. 2017. WESTERN HERP PERSPECTIVES – Alien-Invasoren – zu 100% böse? Reptilia (Münster) 22 (125): 60-61 Macey, J. Robert; Jennifer V. Kuehl, Allan Larson, Michael D. Robinson, Ismail H. Ugurtas, Natalia B. Ananjeva, Hafizur Rahman, Hamid Iqbal Javed, Ridwan Mohamed Osman, Ali Doumma, Theodore J. Papenfuss 2008. Socotra Island the forgotten fragment of Gondwana: Unmasking chameleon lizard history with complete mitochondrial genomic data. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 49 (3): 1015-1018 Machts, Tobias 2014. Der physiologische Farbwechsel bei Chamäleons. Draco 15 (58): 24-37 Meerman, J. & Boomsma, T. 1987. Beobachtungen an Chamaeleo calyptratus calyptratus DUMÉRIL & BIBRON, 1851 in der Arabischen Republik Jemen (Sauria: Chamaeleonidae). Salamandra 23 (1): 10-16 Meshaka Jr., Walter E. 2011. A RUNAWAY TRAIN IN THE MAKING: THE EXOTIC AMPHIBIANS, REPTILES, TURTLES, AND CROCODILIANS OF FLORIDA. Herp. Cons. Biol. 6 (Monograph 1): 1-101 Mocquard, F. 1896. Chamaeleon calcarifer, PETERS et Ch. calyptratus, A. Dum. Bull. Soc. Philomath. Paris (8) 7 (12): 36 Necas , P. 1991. Einige Anmerkungen zur Biologie von Chamaeleo calyptratus. Mitteilungsblatt AG Chamäleons 3: 3. Necas, Peter 1991. Bemerkungen über Chamaeleo calyptratus calyptratus Dumeril & Dumeril, 1851. Herpetofauna 13 (73): 6-10 Necas, Petr 1997. Chamaeleo calyptratus DUMÉRIL, &, DUMÉRIL, 1851. Sauria 19 Suppl.: 389–394 Necas, Petr 1999. Chameleons – Nature’s Hidden Jewels. Edition Chimaira, Frankfurt; 348 pp.; ISBN 3-930612-04-6 (Europe) Nielsen, S. V., Banks, J. L., Diaz, R. E., Trainor, P. A. and Gamble, T. 2018. Dynamic sex chromosomes in Old World chameleons (Squamata: Chamaeleonidae). J. Evol. Biol., DOI: 10.1111/jeb.13242 Peters, W. C. H. 1870. Nachtrag. Chamaeleo calcaratus n. sp. Monatsber. K. Preuss. Akad. Wiss., Berlin 1869: 445- 446. Peters, W. C. H. 1871. Beitrag zur Kenntnis der herpetologische Fauna von Südafrika. Monatsber. K. Preuss. Akad. Wiss., Berlin 1870: 110-115. Rogner, Manfred 2014. Inzwischen ein Terrarien-Klassiker: das Jemenchamäleon, Chamaeleo calyptratus. Draco 15 (58): 76-79 Rogner, Manfred 2014. Chamäleons im Terrarium. Draco 15 (58): 6-22 Rovatsos, Michail; Marie Altmanová , Martina Johnson Pokorná , Petr Velenský , Antonio Sánchez Baca Orcid and Lukáš Kratochvíl 2017. Evolution of Karyotypes in Chameleons Genes 8(12): 382; doi:10.3390/genes8120382 Schmidt, A. 2016. Beeinflussung des Farbwechsels beim Jemenchamäleon (Chamaeleo calyptratus) und beim Madagaskar-Riesenchamäleon (Furcifer oustaleti) durch unterschiedliche Faktoren Reptilia 21 (119): 34-41 Schmidt, W. 2001. Chamaeleo calyptratus – Das Jemenchamäleon. Natur und Tier Verlag (Münster), 80 pp. Schmidt, W. 2009. Chamaeleo calyptratus – Das Jemenchamäleon, 6. Aufl. Natur und Tier Verlag (Münster), 95 pp. Schmidt, W.; Tamm, K. & Wallikewitz, E. 2010. Chamäleons – Drachen unserer Zeit. Natur und Tier Verlag, 328 pp. [review in Reptilia 101: 64, 2013] Schmidt, Wolfgang 1996. Chamaeleo calyptratus. Reptilia 2 (8): 61-64 Schneider, C. 2006. Nachzucht des Jemenchamäleons (Chamaeleo calyptratus, DUMÉRIL & DUMÉRIL 1851). Elaphe 14 (2): 23-31 Sindaco, R. & Jeremcenko, V.K. 2008. The reptiles of the Western Palearctic. Edizioni Belvedere, Latina (Italy), 579 pp. Sindaco, Roberto; Riccardo Nincheri, Benedetto Lanza 2014. Catalogue of Arabian reptiles in the collections of the “La Specola” Museum, Florence. Scripta Herpetologica. Studies on Amphibians and Reptiles in honour of Benedetto Lanza: pp. 137-164 Steindachner,Franz 1903. Batrachier und Reptilien von Südarabien und Sokotra, gesammelt während der südarabischen Expedition der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Sitzungsb. Akad. Wiss. Wien, math.-naturwiss. Kl., 112, Abt. 1: 7-14 Tiedemann, U. & M. TIEDEMANN 1992. Chamaeleo calyptratus Jemenchamäleon. Mitteilungsblatt AG Chamäleons 5: 3-4 Tilbury, C. 2010. Chameleons of Africa: An Atlas, Including the Chameleons of Europe, the Middle East and Asia. Edition Chimaira, Frankfurt M., 831 pp. Tilbury, C. R. & Tolley, Krystal A. 2009. A re-appraisal of the systematics of the African genus Chamaeleo (Reptilia: Chamaeleonidae). Zootaxa 2079: 57–68 Tilbury C.R. & Tolley K.A. (2009b). A re-appraisal of the systematics of the African genus Chamaeleo (Reptilia: Chamaeleonidae). Zootaxa 2079: 57–68 (2009). ISSN 1175-5334 Uhlhaas, M. & P. Pohlscheid 2010. Der Schulzoo des Collegium Josephinum Bonn. Reptilia (Münster) 15 (86): 76-79 van Hoof, J. et al. 2006. Kameleons, een fascinerende hobby. Lacerta 64 (5-6): 1-96 Van Tiggel, Henri 1996. Chamaeleo calyptratus(Duméril & Duméril, 1851). Terra 32 (2): 47-48 Werning, H. 2015. Jurassic World im Wohnzimmer. Mini-Dinos für das Terrarium Reptilia (Münster) 20 (114): 26-37 |

|

Picture Copyright |

Chameleondatabase.com |